The universities and academies have a particular and important role in shaping our societies. Their task is to autonomously pursue the truth, to provide the highest possible education and research that is peered globally, and further on to disseminate their activities to contribute to the dialogue with the society1. The foundations of higher education may be understood both as building frameworks for knowing better, becoming more skilful, and simultaneously as laying the soil for the individuals to mature by advancing their self-knowledge. All of these aims to nourish the virtues, so that an individual may become a responsible actor within the community. In order to achieve these, the higher education is based upon the idea of academic freedom, as being an autonomous forum for critical thought and expression that is liberated from the economic and political influences, in order to foster the society’s development towards the good. The academic freedom has also other connotations, as it originates from the scholars’ liberty for mobility to enable intercultural discourse. The higher education is thus inherently relating to the society internationally.

Higher education is always progressive by nature, related to time, and in constant flux. The institutions are historical build-ups where the disciplines are living traditions and their knowledge is constantly accumulating. The society, which higher education interacts with, has its past, and lives in the present. The objectives of knowing better and maturing are always future oriented, as something in becoming. And eventually higher education produces graduates as members for the tomorrow’s society in the making. Even though some of these fundaments of learning may evolve slowly, every era urges to be acclimatized to the prevailing conditions. Architecture and design span historically all the way to early human settlements and to tools in the wake of agriculture. Obviously, our contemporary habitations and devices could not be more dissimilar. Still the higher education structures itself to bridge between these two, and then further stretches out to the yet unknown future. Without being too extreme, it is significantly different to study architecture and design in the 1930s Norway than it is in 2020s Norway. If one would for example consider a learning process of investigating a chair, it is not unrelated because the understanding of sitting would have changed that much over the years, but because the world around us is dramatically different. Just to begin with, the concepts of consumption, work, materiality and making have all gone through paradigm shifts, and have therefore ontological impacts to the chair in question.

These ever-evolving inquiries are the bread and butter in the higher education, and the dynamic relationship to the circumstances is an essential quality of the academia.

The disciplinary structure in higher education provides for diverse schools of thought, practices and ways of knowing distinct forums of exclusiveness. This plays an important role for specialisation as those with similar interests are able to preserve and accumulate a specific collective knowhow. It even further emphasises the allied professional identity building through guilds and a like, which may lead to positive sense of belonging and peer support for striving the disciplinary establishment, which may even be bound by legislations.

But the vastness of things and the diversity of ways of making sense, makes these categorisations eventually to fall short. Architecture and design are good examples of fields that can be considered as so-called weak disciplines2. This means that particularity of architectural and design knowledge, is that it is ambiguous and manifold, and also an amalgamation of several other ways of knowing, that may belong to other disciplines such as physics, biology, geography, sociology, medicine, economics, politics… etc. But this fundamental ambiguity in itself is not a weakness, but rather quite the opposite, a strength in these fields of study, as it fosters the specific ways of knowing to be adaptable and in continuous flux. This does though challenge the higher education’s common disciplinary structure, and also the vocational establishments which are often based on mechanics of control for quality assurance rather than blurring boundaries for scouting the unknown territories. Further on our current global issues, the foreseeable megatrends, such as urbanisation, digitalisation, climate change with resource scarcity, sociodemographic change and restructuring of economic systems, all imply to so called wicked problems. These are challenges with high level of complexity that have no singular solutions, and even the articulation of the “problems” are difficult to pinpoint. In the past decades this has led to a general assessment whether the disciplinary silos are hindering an adequate means to make sense of these complex issues, which span over several branches of knowledge. The multidisciplinarity and the various crossovers have brought us alternatives to view the knowledge creation beyond solitary fields of study. All these parallels well with the architecture’s and design’s intrinsic values.

It is fair enough to say that higher education is in crisis, as simultaneously the ever- increasing amount of information is available to us all, and the academic canon is no longer the sole source of knowledge. Moreover, the supercomplex world with the highest degree of uncertainty challenges our ways of thinking, as how to foresee what knowledge and which skills – the very foundations of the higher education – would become meaningful in that unknown future3. As most professions will have to be radically redefined and, in many cases, become even redundant, the education within those fields has to re-establish their raison d’être. The neoliberalism and the New Public Management have confused this situation further. On one hand there are expectations that research and education should be more directly applicable for providing innovations to the society’s needs, and on the other hand those intentions and results should be measurable for their impact assessment. These requirements are not only regressive and contradictory to the given tasks, but also a very shallow understanding of the complex and ambiguous world we are in. Even with good intentions to address these challenges, the alternatively proposed 21st century skills have also faced criticism, as too often defining rather narrow favourable outcomes, and competences that rather try to match some of today’s needs than those abilities for approaching the unknown, and thus follow the neoliberal utilitarian mantra. The designers’ mindset can with ease precede such prejudices, by being generously open-ended.

Kunsthøgskolen i Oslo has now been implementing its art and design education for over 200 years. The origins of the institution dates back in the foundations of the Royal Norwegian Drawing School founded in 1818. The roots are in the multidisciplinary art, architecture and craft traditions, where drafting both architectural spaces and furniture took place in the core of the studies. The more implicit history of Interior Architecture and Furniture Design is somewhat younger and can be pinpointed to architect Arne Korsmo in the mid 1930s, when he established the spatial art and furniture drafting as their own teaching. These two courses were taught paralleled from the very beginning, and the Norwegian model came to tie the Interior Architecture and Furniture Design together as a joint programme. Even though the fields may have somewhat different practices and industry models, the alternative pathways have shared a similar approach towards the human-centred design, the optimistic attitude for improving things for the better. The close connection to making has always provided in depth methods for investigating subjects in first-hand, whether those are socio-spatial encountering, tactility of the experience or processes of shaping the matter.

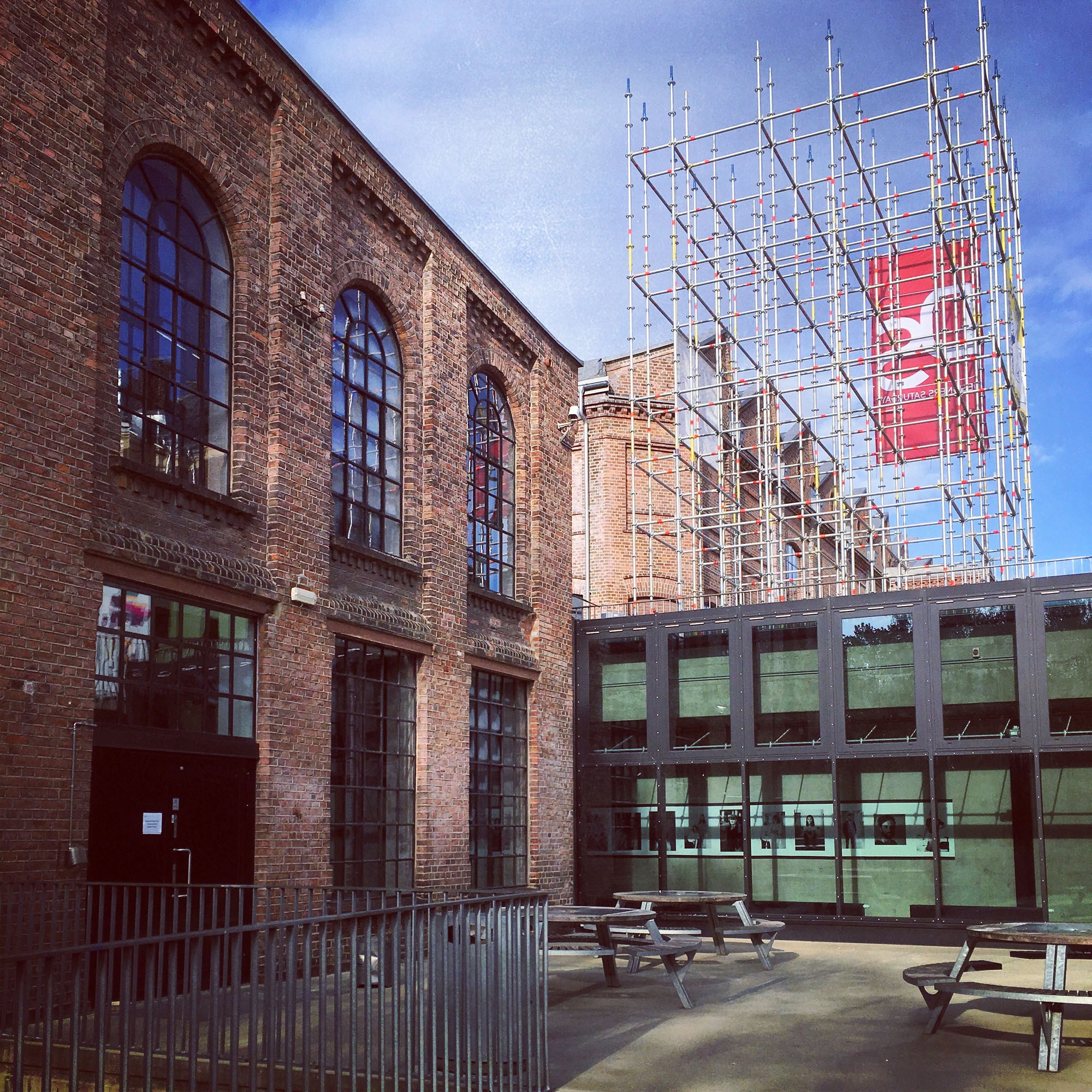

If the disciplinary boundaries are being blurred, the needed skills for the future remain unknown and the professional control mechanisms are irretrievably outdated, and the more sensible post-humanism takes a foothold, how could one start to establish still an educational programme, such as Interior Architecture and Furniture Design? Would there be any specific and intrinsic ways of knowing for these fields? I have tried to elaborate my thoughts on this in my article “What if interiors”4. My take has been to distance us away from the industry and guild silos, which work with segregation as their modes for differentiation. The cloistering will not fortify the fields, but eventually weaken them as inbreeding makes them less resilient. My approach is then rather to celebrate the disciplines’ ambiguity, and to proudly claim the blurry in-between and periphery territories as the natural states of existence. The vagueness thus becomes the desired condition of being. To be concerned about the spaces and things, as ways of making sense and inhabiting this world, becomes about the particularities of the encountering. Of us, in space and time. The typological classifications and inside-outside debate become obsolete as our engagements may occur where-ever. But the qualities of those meetings are not what-ever. They are specific and dynamic. It is in this interiority, in the very profound essence of those instances of spatiality and matter, that our abilities flourish. These are not some technics, but dispositions, our attitudes to approach the world. There are neither any skillsets for that, but rather one needs the full arsenal of means. And those may well be invariably novel and unique. This in return renders the way one should assess what the teaching and learning ought to be. The didactical modus operandi is ill-fitted with ambiguity and not-knowing. The pedagogy in our fields thus is bound to become very much like the practice itself5. To be in a dialogue and to have the will to listen, to learn and to engage through experimenting. The referred crisis of the higher education gets converted into the essential quality of our disciplines, where learning transpires in multiple ways; inside, outside and in-between the institutional boundaries. Our future guilds shall follow and knock down the pretentious borders to salute the professional heterogeneity.To bridge from intent to reflection, I wish to bring forward our key activities, and where we were in 2019. Our main event of the year was the Designers’ Saturday happening, where we played an active role in initiating and hosting the first so-called “Designers’ Saturday Academy”. The DSA was designed to facilitate an umbrella for numerous activities bringing together all the Norwegian higher education institutions in design, young designers and the respective industries. Some highlights were the COOP, in which companies collaborated with students, the Design Talks with international keynotes and the Best Talents where the emerging new designers got awarded. KHiO graduates excelled in the latter by winning all the prizes, Mari Koppanen the 1st and 2nd, and Nina Tsybolskaia the 3rd. The event architecture for the DSA was designed by KHiO alumni Martine Scheen and student Sindre Buraas. Some of the other main undertakings included the continuation of our long-term DIKU-funded international material-cultural research project, “Connecting Wool”, together with Tama Art University in Japan. Also, our study programme was a devoted participant in the Oslo Architecture Triennale, especially within the academia initiative titled “Dealing With It” together with architecture and design students around the world, examining transformation case-studies in Oslo.

Regarding the graduates for Master of Design from the past year, the students have brought forward a broad range of issues. Aida Brillas’s project “Life After Water” speculates on a scenario how to inhabit Oslo once heavily flooded as the consequence of melted polar glaciers. Birgitte Rødland Haga’s, project “Konfrontasjon” stages impediments within the eating disorders for public debate through participatory experiences. Mari Koppanen material investigation on fungi also addresses the complex issues of cultural heritage and misappropriation. Her project “We Grew Together» also won on top of the Best Talent prize, the award as KHiO’s Best Design project in 2019. Fatimah Mahdi’s project “Ord som Puster” elaborates on cultural clashes and confrontations in our society from the Third Cultural Kid perspective. “Havfolket” by Tuva Malm studies the Northern Norway’s ancient island- cultures, and how these are facing the inevitable 21st century mutations caused by tourism and climate. Laura Peña digs deep in her project “Inside Down”, both literally to the medieval Norwegian mining tradition and mentally to the core of being a human, to the myths and legends. Her ultimate underground interiors not only host the treasures of humankind, but also no less than the dragon itself. Vilde Rapp Riise project “Ospers” surveys the Norwegian ecosystems to recognise emerging potentials; the crafting of aspens meets the harvesting of oysters. Our immense existing building stock comes up against obstacles of reuse in the rapidly changing society. Martine Scheen’s project “Bevar Meg Vel” addresses this through her transformation proposal, where the nature starts to take over again. Her project won this year’s Statsbygg Award. Stine Helen Sletvold colours and animates vividly the hidden maze of urban interiors of Oslo’s Kvadraturen area in her project “Hemmelige Offentlige Rom”.

Mads John Thomseth confines himself to the workshops and examines the making practices in his collection of ‘Nice Shelves’. Our electronic identities are scattered around the ubiquitous rhizomes of servers and clouds, and once we decease those bytes are left behind us. Nina Tsyboulskaia elaborates on the complications of longing and the traces of death at the digital era in her project “Over the Deadline”.

To conclude. As I was asked to write this text earlier this year, it happened that I undertook the task during the quarantine of the COVID-19 pandemic. Without knowing the full extent of this incident, it can already easily be said, this to be one of the most dramatic global crises so far in the 21st century. The ramifications of this outbreak are truly unprecedented and unpredictable. To be confronted by these perturbations caused by the incident at the time of writing, it ironically underlines my take on the educational ambivalence. On the day of the COVID-19 lockdown in Norway, we were one week away finishing our most advanced project so far to be premiered at the Design March in Reykjavik. It is an intensive joint project together with one of the most prestigious global design offices, IDEO. Our task has been no- less than investigating the new modes of practice-academia collaborations on the level of nation building; how strategical design may address whole societies, how future-orientated optimism may steer nations within the supercomplex worldwide community and how the design’s tangible and experiential means help us prophesy the good ahead of us. The project is titled “New Norwegian-ness”. Our design research has enabled us to distinguish the well- being in us and in our cultures, and to speculate how could that well-being lead us in the uncertain tomorrow. The core conclusions have been so far, by being transnational we can celebrate our differences in order to act together. This may happen very locally with slowness, and our abilities for empathy raises above all. This we knew already before COVID-19 hit us. And now we have to act on what we believe in, encountering the ambiguity in the world with grace.

Kunsthøgskolen i Oslo. Avdeling design. Interiørarkitektur og møbeldesign